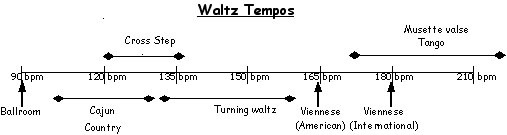

A chart on waltz tempos from Dance styles:

These are comments culled from Fiddle-L and responses

to the question "What makes a good contra dance band?" on the newsgroup

rec.folk-dancing, from the article

Contra and Square Dance

Playing by Phil and Vivian Williams (their remarks used with

permission), and

Tune

Talk for Contra Dances, a forum on

Mandolin Cafe, as well as from

various contra dance musicians and callers, and from contra dancers. Some

comments were very useful, some were obvious, and some were obviously in

response to bad experiences. I have arranged them according to topic.

To find the complete thread on rec.folk-dancing, search

Google

Groups using this search key: +what +band +great +contra

group:rec.folk-dancing. To search the archives of Fiddle-L, go to

http://listserv.brown.edu/archives/fiddle-l.html

Donna Hébert quoted with permission

Back to Contra Dance Music: A Working Musician's Guide

| Choice of music |

The band is playful with the choice of music:

"Choosing the occasional rag or even a march. Even a folk rock song played

so it is "square" can be a lot of fun."

Some like it when a band focuses on a particular tradition, such as New England,

Québécois or Appalachian. One person wrote of the importance

for a band to know and use the classic tunes of their tradition. They don't

need to play the classics all the time, but once in a while is good. And,

the band should try to maintain the nature of the tradition that the music

comes from, even when deviating from it to a great degree.

Have a wide repertoire. Some callers like a band to be able to play anything

they request, but we all know that's not always possible.

For a discussion of tune medleys, see Choosing Tunes

for Contra Dance Medleys.

| Instrumentation |

Love the accordionists.

Percussion adds to the sound, but avoid rock & roll type drumming because

it can obliterate the underlying triplet (swing) rhythm of traditional

music.

"No didgeridoos."

| Musicianship |

Being a dancer as well as a musician is very helpful. Many people wrote that it is essential that band members all dance (and dance because they want to and not out a feeling of obligation), at least some of the time. This gives the band insight into what dancers need. One person quoted Duke Ellington:

| "Dancing is very important to people who play music with a beat. I think that people who don't dance, or who never did dance, don't really understand the beat. ... I know musicians who don't and never did dance, and they have difficulty communicating." |

"Musicianship can be acquired in a number of ways,

whether by formal lessons or lots of exposure (usually by both), but it all

boils down to one thing: PRACTICE. That would refer to both individual practice

and band practice. ... The bands that can do the complex arrangements can

do so because of their understanding of and complete appreciation of the

fundamentals. Just like dancers-- those twirls only work if you know where

and when they belong, and when they do not belong."

Don't play exactly what's written in tune books.

The things most frequently mentioned as necessary were a steady

tempo, a strong

beat, solid

rhythm, and good, clear

phrasing.

| Tempo |

Not only should the tempo be steady, but the

band members should agree on the tempo.

If you have trouble with tempos, learn to dance. If YOU can't dance to it,

can anyone else? You don't have to be an expert dancer, but if you can dance

pretty well, you'll know what tempos to play.

Mary

McNab Dart writes this about tempo:

"A good dance tempo is one that is slow enough to allow the dancers to dance

comfortably to the music, but that provides enough energy to give lift to

their feet and support to their natural momentum. ... Rushing to keep up

with the music is not fun. A tempo that is too slow, on the other hand, makes

it hard to accomplish figures that require a degree of momentum, such as

the "swing." ... A very involved dance with a number of precisely timed sequences

needs music that is not too fast."

From Donna Hébert: Tempos vary for dances and tune meters. Jig time

6/8 can move a lot faster than reel time 2/4.

Suggested tempos are:

| Contras: | 114-116 bpm; also 112-118 bpm. At tempos higher than 120 bpm, the dance becomes merely an aerobic workout, and the figures can't be done in an enjoyable fashion. |

| Squares: | 120-130 bpm |

| Waltzes: | 132 bpm; also: 115-165, average:

140 bpm A chart on waltz tempos from Dance styles:  |

| Hambos: | 138 bpm; also: 120-144, average: 132 bpm |

Donna Hébert noted that some callers now

want tempos around 128-132, while 120-124 is better for most contras. Slower

tempos are more forgiving of beginning contra dancers and also allows the

band to "groove more and worry less about which notes to leave out of some

fingerbustin' tune." Donna also may speed up a little on the last tune of

a medley when the dancers really have the figure and the caller has stopped

calling.

Jim

Nollman, in a forum on

Mandolin

Cafe says that "I agree that 120 is a normal "fast tempo" and though

my bands generally play reels there it gets wearing for us and the dancers

and so we like to vary things. 110 is a normal "relaxed tempo" and 115 is

a good medium tempo. We might get up to 126 and at 130 it's really too frantic,

though I think we have probably gotten that fast on occasion but probably

only the last time through the last dance of the evening."

| Beat |

A good strong down beat is necessary. So is

a good backbeat.

From Phil and Vivian Williams: The music has a lot to do with the dancers'

perception of energy and fatigue. Spirited playing with a well defined, punchy

down beat and a "chopped" chord up beat right in time will give dancers a

lift. So will playing the tune simple with lots of drive, as will straight

ahead unison playing by the lead musicians. Sloppier timing, syncopations

in the backup, letting backup chords ring, getting away from the melody into

less distinguishable variations, playing softer and with less drive, all

will give the dancers somewhat of a "let down" feeling and permit them to

dance more relaxed with less push. The change from one style to the other

can be an effective tool to shape the dancers' perception and give them a

chance to relax when they might be getting tired, but bring them back to

full energy by the end of the dance. Start the dance with spirited, straight

ahead playing, right on the beat, right on the tune, and uncluttered. In

the middle of the dance, disintegrate the playing slightly with the lead

playing variations, longer sustained chords in the backup, a few syncopations,

and more relaxed playing. Done right, you can see the dancers relax, start

smiling, and realize that they don't have to exert themselves quite so hard.

After letting them cruise for awhile, tighten up the playing, get back to

the basics of good, simple, on-the-beat backup and straight ahead lead. Done

right, you will see the energy come back to the dance for a wind-up that

leaves the dancers breathless and excited. When the dancers start whooping

and hollering, you know you have pulled off this trick just right.

From Donna Hébert: Contra music is not accented on the 1 and 3 beat,

but exactly the opposite, the 2 and 4 beat. It's not the BOOM, but the CHUCK

that gets accented, creating a natural syncopation that drives the music.

Oldtimers in New England from the thirties to the sixties played "straighter,"

with downbeat accenting.

Donna often refers to the "groove," which she defines as "the agreed upon

(often silently) common rhythm the group plays in - where they put the beat,

swung (anticipating the downbeat) or unswung. If all are accenting the beat

in the same manner and on the same spot, groove happens and the music and

dancing occurs with much less physical effort." "Groove is a non-verbal group

agreement to sit in the same place on the beat, all giving it the same slant."

| Rhythm |

The rhythm should be consistent and danceable.

| Phrasing |

Good phrasing communicates to the dancers where

figures in the dance begin and end, and the band should maintain phrasing

even when "getting wild" or changing tunes. One person said, "I don't want

to wonder there the ladies' chain starts; the music should tell me, every

time through."

Another person wrote that the dancers don't have to understand what phrasing

is in order to benefit from it, but the less they understand it, the more

they need it from the music. "Good phrasing means never having to wonder

'are we there yet?'."

Some members of Fiddle-L (both fiddlers and callers) believe many Irish tunes,

although good music, often don't have the phrasing or stylistic characteristics

necessary for good dance music. Examples are tunes with ambiguous endings

or in which "beginning of the tune was phrased in such a way that the first

measure or two felt like lead-ins rather than like an emphatic beginning

of a tune."

Sten Swanson writes that

a strong and obvious beat are necessary. It is possible to dance just following

the tempo, but occasionally dancers need to "resynchronize" with the phrase.

His suggestions are to

1. use strong or obvious phrasing at the end of an 8- or 16-beat figure;

2. emphasize phrase endings with small pauses, longer notes, obvious harmonic

cadences, or instrumental changes going into the next phrase;

3. choose tunes that emphasize dance figures (See also

What types

of tunes work and what type don't work).

4. keep the beat obvious when improvising.

Innovation should be used, but not to the detriment of maintaining the beat

or phrasing.

One person likes a "pulsing, throbbing, surging, energizing flow" from the

band.

| Improvising: Remarks made by Donna Hébert |

In jazz, you make up a whole new

melody over the chords. In fiddling, you drum a new

rhythm over the melody. The bow becomes a drumstick. Because

contra dancers dance to the musical phrases and need some recognizable melody

to tell where they are in the dance, you don't completely rewrite the melody

as in jazz, just restate it with a little different rhythmic accent each

time. Some improvise licks in a tune get used almost every time I play the

tune, just not in the same place in the tune every time through. And ALL

improvisation is subordinate to the groove and serves it.

To improvise, take the tune down to its bare bones (usually quarter or eighth

notes instead of sixteenths for a reel) and rebuild it with a slightly different

rhythm each time.

While one member of the band is improvising, the others can be doing rhythmic

backup, counter melodies, and altered harmonies, depending on the sort of

tune being played and the skills and conventions are among the musicians

playing.

Ornaments (rhythmic and melodic) are largely dictated by regional styles

and can be used. Ornaments for a style are fairly congruent within that style

but these ornaments are used at the fiddler's inclination on any given tune.

I use the same ornaments in many of the French tunes I play, but not all

in the same tune, as different ornaments lend themselves to different types

of melodic phrases. Ornaments are often used to establish rhythm as well,

and their placement can change between one repetition of the tune to another

to keep the tune interesting to dance to.

| Backing up the melody: Remarks made by Phil and Vivian Williams |

The backup has a major role in shaping the spirit

of the dance. Dancers need good rhythm. The first duty of backup players

is to provide solid rhythm, rather than demonstrating their range of pyrotechnic

skills. The most effective guitar backup for a straight time tune is simply

a flatpicked bass note on the down beat followed by a dynamic brush across

the chord on the off beat. A solid, dynamic off beat actually will give the

dancers a greater "lift" in most cases than a heavy accent on the down beat.

Being conscious of bass lines and developing moving bass lines appropriate

for the tune is a major role for guitar and piano players. Piano backup is

best with just a bass note or octave on the down beat, and the treble chord

on the up beat. Piano players sometimes like to syncopate their playing or

use other ornaments. These should be used with a high degree of discretion.

Not only can this throw off the lead player, it can stall out the forward

momentum of the music and thus of the dance.

Backup players also need to be aware of the chord and inversion or position

that best complements the lead. The music sounds best and supports the lead

best when all the backup players agree on the chords to use. Generally, using

straight ahead major chords in a major key tune and minor chords in a minor

tune will provide the greatest sense of forward motion. The substitution

of "modern" chords for basic chords often is detrimental to the mood and

movement of the music and must be done with caution.

Lead players sharing the lead duties with other lead players need to learn

how to provide effective backup when they are not playing lead. For a fiddler,

this usually means playing drone notes, offbeat "chunks," harmony, or nothing.

It is better to have nothing than a counter-melody which adds to the clutter.

For an accordion player, backup means playing bass notes and chords. Flute

players can play harmonies and obbligatos, but really need to watch it as

the high pitches can clutter the sound fast. Mandolinists should play off

beat chords. Above all, the lead player who is not currently playing lead

needs to be aware of when they might be cluttering up the sound and interfere

with the lead player's ability to play effectively or to be heard. Unison

playing can be quite effective. It helps if the band uses musical arrangements

that minimize the clutter and maximize the ability to hear the lead clearly

and provide strong rhythm. If you do your arranging on the spot, keep your

eyes and ears open and be prepared to jump in and play lead or jump out and

play backup on verbal and non-verbal cues from the other band members

| Novelty |

Keep the integrity of the tunes even when doing

novel things, like using unusual instruments, unusual rhythms, pauses, stops,

harmonies, counter melodies, sung verses, etc.

When it works it's great; when it doesn't work, it breaks the connection

between the band and the dancers.

Overuse of novelty can contributes to sloppy dancing. "An effect is not

"creative" anymore when it's used too often. And, like superfluous twirling

on the part of dancers, it can interfere with teaching people to value what

*really* matters - (tightness, working together, connection, etc.)

| Interaction between the band members |

One person suggested that bad vibes between

musicians, even when they're trying to ignore them in the band, are communicated

to the dancers. The writer continued that the dance music is the best when

the band has fun playing together.

The band members should listen to each other and communicate with each other

while playing.

| Interaction with the caller |

Set up communication signals early in the evening

between caller and band.

The band should work with the caller to set the right tempo. It's OK to ask

the caller what tempo s/he wants.

Pay attention to the caller and what s/he is trying to achieve with a particular

dance. Ask whether s/he prefers reels or jigs for the dance. Some figures

in the dance might work better with a reel than with a jig. (See

What types

of tunes work and what type don't work.)

From Donna Hébert: ask the caller where the "hook" is in the dance

- it could be a balance at the start of either A or B parts, or another,

smoother figure.

From Phil and Vivian Williams:

From Carol Ormand, a caller and contra dance musician:

From Eric J. Anderson:

| Interaction with the dancers |

From Donna Hébert: The caller's job is

to pay constant attention to the dancers, while the musicians do so peripherally

while they focus more on the music.

"Some bands just make the music fit the dance and the dancers like a glove,

while some play wonderfully but would be better in a concert setting."

When the band watches the dance floor, they can adjust phrasing and tempo

to supply stronger musical support when needed, possibly even before the

caller requests it!

This same person wrote that it is important for her, when booking bands,

to keep in mind the bands that the dancers like to dance to.

One person said, "... bands that watch the dancers are more to my liking

than those who do not."

| Miscellaneous |

Good energy and a sense of fun.

Quiet during the walkthrough.

From Phil and Vivian Williams: Socializing, running through tunes, and obtrusive

tuning while the caller is trying to conduct instruction or a walk-through

can be very distracting, both for the caller and the dancers. Try to be as

unobtrusive as possible until it is time to play. Talk only as much as necessary

to get set up for the next dance set.

Related to the first point under communication with the dancers is the feeling

that the band that wants to be a functional dance band is more effective

than one seeking to be an artistic show band.

Be a contra dance musician for love. Well, from experience I can add: don't

do it for the money!

"Never play for dances, it will ruin the way you play the fiddle"--an

old-time fiddler quoted on Fiddle-L.